As soon as I find someone who claims to have even passing knowledge of both Grant Wood and Diego Rivera, I’m going to make this bold statement: “You know, if you think about it, Grant Wood was really the Diego Rivera of the United States,” and see what comes out of it.

I will concede at the outset that this post will be written with the aid of hazily remembered facts and an imperfect understanding of the stylistic nuances of the visual arts (read: please don’t fact check this post). That being said, in quickly cobbling together the little that I know about the styles, eras, and politics of the two iconic painters, I think you’ll agree that the similarities are uncanny.

Where to start? Both were born in smallish, land-locked towns in the Western Hemisphere; Wood in Anamosa, IA and Rivera in Guanajuato, Guanajuato. Both began painting at a very early age and continued to study the arts through high school and college. Both went to Europe during the Impressionism craze and painted various impressionisty/cubistical looking pieces that hardly even resemble their more famous works. And for both Wood and Rivera, it was after being exposed to these colonial influences that both painters ended up finding their unique voices that, in many ways, were a reaction to and a rejection of these continental influences.

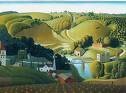

Rivera returned to Mexico and began to paint what he knew: the peasants, the indigenous peoples, farmers, laborers using bold, bright colors and simple figures. Wood returned, stepped out of his home near Iowa City, and began to paint scenes of farms and country folk performing everyday tasks using a similarly bright and bold color scheme on his canvasses, although usually with a tad more attention to detail.

And there’s more. They were also both ardent lefties. Rivera was an admirer of Emiliano Zapata, from whom the leftist Zapatista rebels (a group still active in the state of Chiapas) take their name, and a member of Mexico’s Communist party. Wood became close friend to Vice President and Iowan Henry A. Wallace, who ran unsuccessfully for President with the Progressive Party after being dropped by Roosevelt for being, get this, too liberal (and over-crazy). Wood even did Wallace’s portrait for a Time Magazine cover that appeared during his glory days. Both artists had successful academic careers teaching painting, Rivera at some University that I can’t remember, and Grant Wood at the University of Iowa.

Appropriate to their politics, both painters also played major roles in New Deal type policies. Rivera was chosen to lead various government funded mural projects when the government was looking to put people to work. Wood became the leader of several major public works art projects in the Midwest during the New Deal.

These appointments makes sense, as both men were proponents of murals as a more democratic form of art. Murals beautified cities and made art part of the landscape of one’s everyday world. They were also major projects and called for the work of many men to complete. Rivera has his murals at, among other places, the Palacio Nacional in Mexico City; Wood has his at, among other places, the Iowa State University Library.

Possibly the most striking similarities between the two mural-painting, revolutionary-loving, farmer-depicting lefties, was their philosophy about painting and art. Rivera revolted against all things colonial: customs, religion, class, cruelty, etc. Wood too revolted, but it was against a different kind of colonialism. He revolted against a blind acceptance of the artistic forms, subjects, and styles that had filtered from the cultural centers in Europe, through the East Coast of the States, eventually to be adopted by the heartland as not just fine art, but the finest art.

In his manifesto Revolution and the City, Wood called this kind of trickle down capacity for artistic creation or appreciation “Cultural Colonialism.” That’s right, the man wrote manifestos. And some critics refer to him and his work as quaint. Quaint people don’t spend sweaty nights pumping out manifestos. Wood took on the art establishment and he won. His victories might have been short lived, but they were on his terms. And at the time, this was revolutionary. To think, a painter in Iowa could step outside of his home, paint the land and his neighbors, and call it Art. The gall.

Of course, of the two, Rivera is viewed as the more revolutionary, probably because 1) he was a communist who participated in Communist revolutions; and 2) he was more overt in his critiques of religion, which always tends to get a rise out of the faithful. Case in point: one of the murals at the Palacio Nacional features a Priest with a bottle of liquor in one hand and a prostitute’s arse in the other. Then again, I still think there is a strong argument that American Gothic actually is a subtle critic on religion and conformity.

But let’s not stray to much from the thesis. When you get down to the heart of the matter, the two aren’t that different. They were both anti-colonialist skeptics who celebrated the simple beauty of the worlds that surrounded them. Revolutionaries both, through and through.

Viva Rivera! Viva Wood! Viva La Revolution!

Diego Rivera: 1886-1957

Grant Wood: 1892-1942

Grant Wood: 1892-1942

5 comments:

Very interesting. I'd like to see this go further. But as for their impressionisticky art? Impressionism was already converted into something else by the time they were both born. Monet was painting his Nympheas (decidedly not impressionist) at the same time that Duchamp put his urinals in the museum. Art overlaps. Was what Wood and Rivera were doing successful? Is it possible for the purpose of art to change or is it always the same?

katy woodford says.

Katy--

You did the one thing that I explicitly forbade people to do at the outset of the post: fact check me.

But seeing as you did, I'll make some edits.

The use of the term "impressionism craze" above was inaccurate, and quite frankly, embarrassing. I'm going to change that sentence to "arrived in Europe and painted various cubisticalical/impresionalistical looking pieces that hardly even resemble. . ." etc. etc.

I hope this fixes the time period problem.

Just to see a bit what I'm talking about, here’s a shot of Rivera’s cubisty looking stuff.

And here’s an image of what I consider to be some of Wood’s impressionistically looking stuff from 1926. As you have capably pointed out, 1926 was well after the birth of impressionism, but to my imperfect eye, Wood still seems to be experimenting with some of the movements more famous techniques . Take a look and get back to me.

Were they successful? Sure. Wood, along with John Stuart Curry and Thomas Hart Benton, is widely considered to be one of the fathers of the Regionalist movement that was going strong between the years of blah blah blah. And Rivera, as it is well known, started what art historians call the “Womanizing” movement, culminating in his romantic relationship with widely celebrated but temperamental surrealist Salma Hayek.

Again. There’s no need to fact check this. I’m pretty sure I’ve got it right this time.

Thanks for keeping me honest Katy. You are missed.

I never accepted the 'terms and conditions' of your blog (nor the box that allowed you to send me travel e-mails, discount watches, or your bi-monthly newsletter, so can it.) But it wasn't my intention to refute your observation, merely just some pondering.

however.

"Successful" in art can mean two things. One, which you admirably tackled, is the commercial and popular approval of artists and their methods. The other is more difficult to qualify, and that is the success of each painting/installation etc., as it gets closer to the truth-with-a-capital-T of what human existence is all about. There are artists who pursue their glimpses of the things that bind us all together into madness (VanGogh, Giacometti) and those that became prosperous while not selling out (Monet, Rembrandt, to an extent). Not every painting the great masters' did were 'successful', but they were able to understand more than the average bear.

As for Rivera and Wood, I don't know. Wood certainly used color well but art seemed to take a turn in the twenties and thirties, and although I enjoy the novelty of it, I'm not sure that most of it holds onto what is meaningful.

how on earth do you have time to write a blog?

Ah..gregory, you are missed as well.

I completely agree.

Post a Comment